BepiColombo Mercury Mission Bids Farewell To Earth

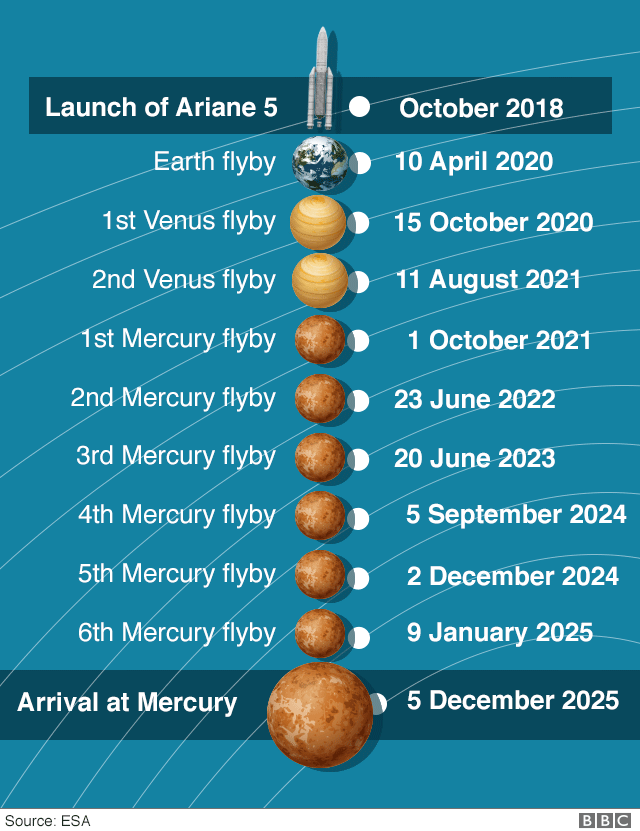

LAHORE MIRROR (Monitoring Desk)–BepiColombo, the joint European-Japanese mission to Mercury, has swung past the Earth – a key milestone in its seven-year journey to reach the “iron planet.”

The gravitational flyby enabled the two-in-one space probe to bend a path towards the inner Solar System and bleed off some speed.

The mission needs to make sure it isn’t travelling too fast when it arrives at Mercury in 2025 or it won’t be able to go into orbit around the diminutive world.

“It would be so nice if we could take an express transfer and then we’d be there in a few months, but that doesn’t work for this mission,” Elsa Montagnon, the flight controller in charge of BepiColombo at the European Space Agency (Esa), told BBC News.

As well as this flyby of Earth, Bepi must perform two similar manoeuvres at Venus and six at Mercury itself to get itself into position..

The only alternative would have been to give the spacecraft a colossal volume of fuel to use in a braking engine. An impractical solution.

Bepi came within 13,000km (8,000 miles) of the Earth’s surface. Closest approach was at about 05:25 BST (06:25 CEST).

It should have been visible in darkened skies in the Southern Hemisphere, although not to the naked eye. A small telescope or binoculars was required.

Anyone who captured a picture was asked to upload the image to this Flickr group, or to post it on Twitter or Instagram using the hashtag #BepiColomboEarthFlyby.

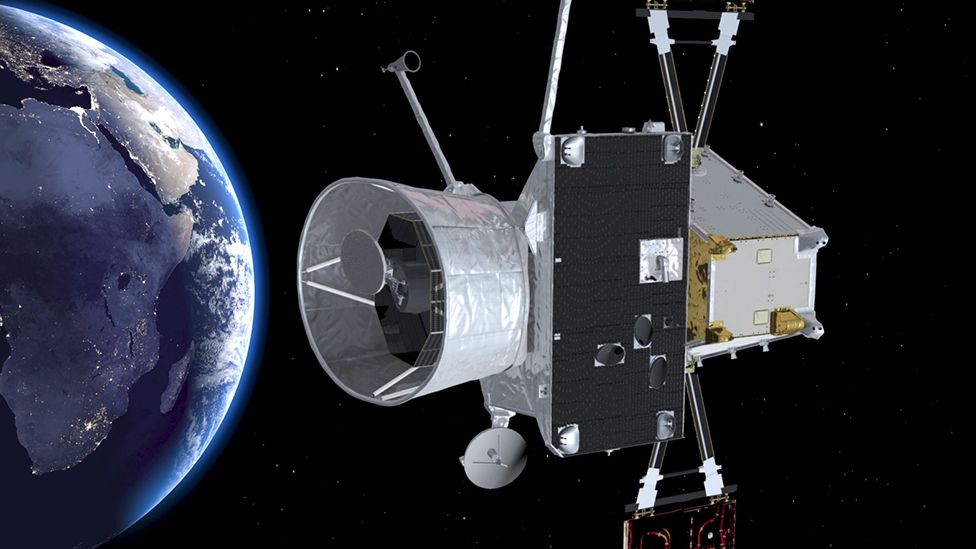

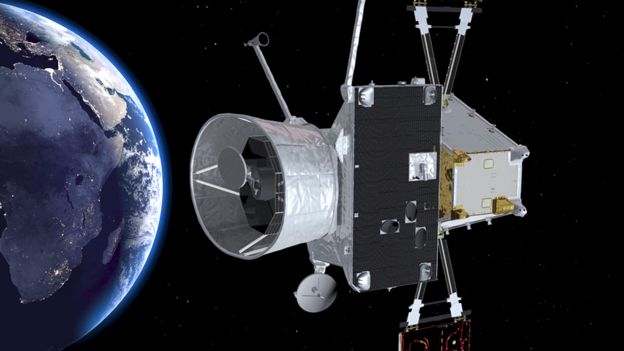

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA

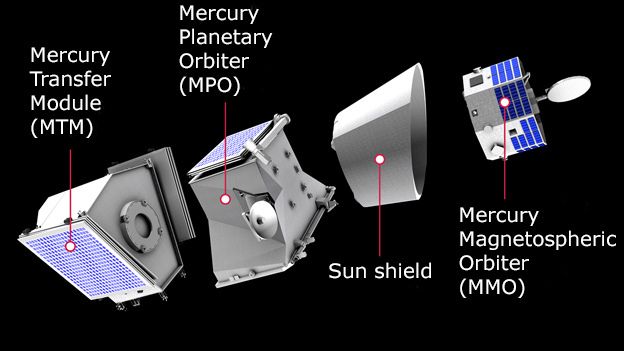

The €3bn (£2.6bn) BepiColombo mission was launched in October 2018. It comprises two scientific satellites – the European Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and the Japanese Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) – that have been joined to a propulsion module for the long cruise.

Not only must the velocity of the spacecraft stack be controlled, but so too must its inclination with respect to the plane of the planets. Mercury’s orbit is offset by 6 degrees from that of Earth’s.

Already since the 2018 launch, the mission has completed one and a half loops around the Sun on its grand odyssey, travelling a distance of roughly 1.4 billion km. By they time it’s emplaced at Mercury and ready to begin science observations, Bepi will have completed 18 loops and covered more than 8.5 billion km.

Mission scientists switched on a number of the duo’s instruments for the Earth pass, to test and calibrate them. Unfortunately, the main camera on Europe’s MPO couldn’t operate because of its position in the stack. But small inspection cameras to the side of Bepi did manage to grab some black & white pictures of the Earth and Moon.

The next flyby will be of Venus in October. For most of the long journey, controllers on Earth will limit communication with the spacecraft to about one contact a week.

“Of course, even when we’re in quiet cruise, there are some maintenance operations to be done with the satellite. So, typically, every six months we are doing a thorough check out of the subsystems and the instruments where we activate units that are normally not active just to make sure they are still functioning okay,” explained Elsa Montagnon.

Image copyrightESA

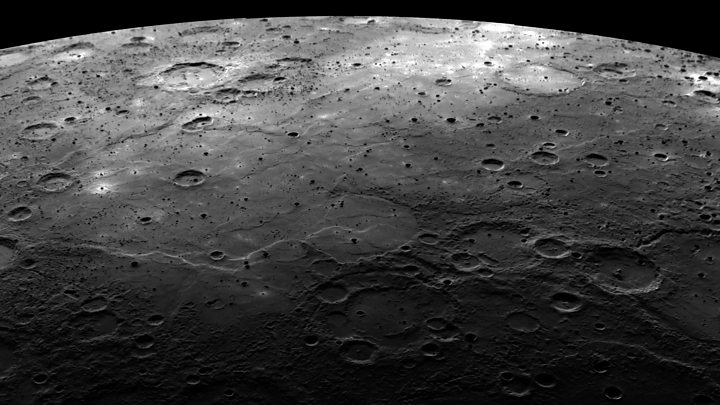

Image copyrightESAWhat science will BepiColombo do at Mercury?

The European and Japanese elements of the mission will separate when they get to Mercury and perform different roles.

Europe’s MPO is designed to map Mercury’s terrain, generate height profiles, collect data on the planet’s surface structure and composition, as well as sensing its interior.

Japan’s MMO will make as its priority the study of Mercury’s magnetic field. It will investigate the field’s behaviour and its interaction with the “solar wind”, the billowing mass of particles that stream away from the Sun. This wind interacts with Mercury’s super-tenuous atmosphere, whipping atoms into a tail that reaches far into space.

It’s hoped the satellites’ parallel observations can finally resolve the many puzzles about the hot little world.

One of the key ones concerns the object’s oversized iron core, which represents 60% of Mercury’s mass. Science cannot yet explain why the planet only has a thin veneer of rocks.

SOURCE: BBC News